Developing a New Drug Candidate: From Nonclinical to First-in-Human

Thank you to Charlotta Gauffin, Chief Scientific Officer at Dicot, for joining us for our recent webinar, “The Road to First-in-Human Trials: Insights from a Real-World Example.”

Thoughtfully and carefully planned nonclinical studies help pave a smooth path toward first-in-human Phase 1 clinical trials. This involves a collaboration between all areas of nonclinical development, including CMC, toxicology, pharmacology, DPMK, and so on, and keeping in mind early a plan that all stakeholders agree to, but that can be amended as you go along, if needed. Here, we share how Cytel and Dicot worked together to conduct the nonclinical studies for the LIB-01 compound, a new drug candidate to target and treat erectile dysfunction, including prerequisites for keeping project plans, delivery of results, and dealing with the consequences of decisions made during the drug development.

Erectile dysfunction is very common: about 50% of men over 40 will experience erectile dysfunction at some level during their life. And it becomes more common as you get older. However, current treatments have several well-known drawbacks, such as side effects, non-responders, and poor responders. And you need to plan your intimate life around an on-demand treatment. As such, there is about a 50% dropout rate, so there is undoubtedly room for improved treatment options.

A new approach to treating erectile dysfunction

The compound that would eventually become LIB-01 was initially known for its history as a folk remedy. Then, Uppsala University Professor Jarl Wikberg identified and characterized the pharmacologically active, yet previously unknown, plant material substances. He was then able to develop a semisynthetic route to synthesize these compounds.

In his drug discovery work, including behavioral studies in animals, he found that the compound had a dose-dependent effect on sexual activity in mice. He could also see that the effect was long-lasting, an attribute of this compound that is very different from other pro-erectile drugs on the market today. With all this early-phase data, the project was ready to become a development project under the umbrella of Dicot, and this is when the Cytel team came into the picture.

Dicot has since moved beyond the original plant material, working instead with a patented semisynthetic molecule to take through the drug development path with the aim of reaching the global market with a registered pharmaceutical drug.

Nonclinical studies: Paving the way to first-in-human trials

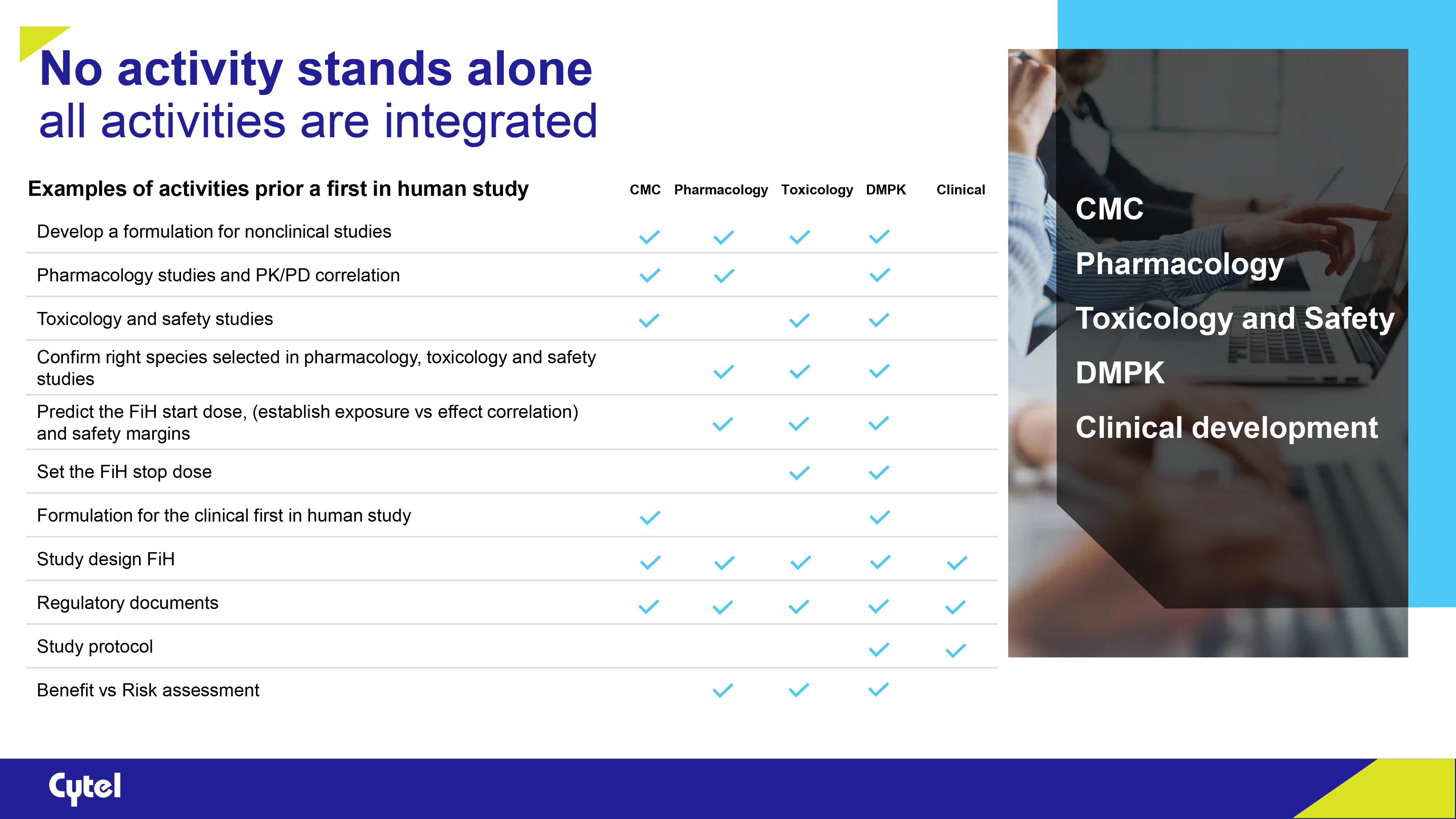

The objective of first-in-human Phase 1 clinical trials is to evaluate the safety and tolerability of your substance in humans, to characterize the pharmacokinetics of your molecule in humans, and to get enough information regarding pharmacokinetics, pharmacology, and safety to be able to design scientifically valid Phase 2 studies. Therefore, it is essential to mitigate risks ahead of time and perform supporting nonclinical activities before administering the first dose.

All nonclinical activities are integrated between disciplines; it’s a collaboration phase. Prior to first-in-human studies, activities include CMC, pharmacology, toxicology, DMPK, and clinical development. Here, we’ll delve into the nonclinical studies leading up to the first-in-human trial and some challenges faced along the way.

Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC): Developing the drug formulation

CMC is a vital part of the process because it’s all about how you get your drug into the body: the formulation and the associated quality attributes and analytical methods of the drug substance and drug product. However, there may be times when you need to switch from one route of administration to another, which might require a reformulated drug product or altered quality attributes of the formulation.

In the case of the LIB-01 compound, two formulations were developed in parallel; while the oral formulation was being developed, which was the intended end product, the subcutaneous formulation was used to drive the project forward, and then a transition was made. Doing the work simultaneously saved quite a lot of time. And this is true as well when developing a placebo. Parallel work will save time if any reformulations are needed.

Pharmacology: Understanding the mode of action and effect of the drug

Primary pharmacodynamic studies, usually divided into in vitro and in vivo studies, determine the mode of action and effects of the substance in relation to the desired therapeutic target. You should start planning and studying the pharmacological effect in animals early, which will determine the doses, the onset of effect, the duration, and if any specific dosing schedules are required. Without a pharmacological effect, you won’t have a project. After the animal studies, we concluded that we had reached a feasible dose, that is, a starting dose for the first-in-human study.

But in this case, we had to factor in the switch between formulations. When designing the studies on oral administration, we were able to use data generated with the subcutaneous formulation, increasing the probability of success for the studies. Still, the question was how the oral formulation would affect the pharmacokinetics of the substance. This data was complemented with oral administration studies. The strategy was verified by scientific advice from the relevant authorities.

Toxicology: Characterizing the toxicological effects

You need to characterize the toxicological effects of your substance before starting a first-in-human trial: What are the target organs? Is there a relationship between toxicity and exposure? And is this toxicity reversible? This preclinical information is used to estimate the initial starting dose, the dose range used, and to find the parameters for clinical monitoring.

Depending on what your project is — the type of substance, administration, therapeutic area, trial phase, and development horizon — the guidelines will set the frame for your toxicological program. It’s important to remember, though, that not all guidelines always apply to your specific project.

Drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics (DMPK): How the body processes a drug substance

DMPK studies focus on understanding how a drug is metabolized and how it behaves within the body (pharmacokinetics) and help assess the safety and efficacy of a drug candidate. DMPK activities differ between molecule entities, but the questions that need to be answered are the same: prediction of the starting dose, dose escalation steps, and stop criterion. All available nonclinical information, such as PD, PK, TK, and toxicology profile exposure effect relationships, must be considered.

While this was a new compound, the pharmacokinetic characteristics of the class of compounds have been studied. Our pharmacokinetic studies in animals with different formulations characterized the exposure. In addition, in vitro studies were performed, such as plasma protein binding and studying metabolites, all of which were necessary to determine a starting dose for the first-in-human study.

Designing the first-in-human clinical trial: Safety and tolerability

To design a clinical trial properly, you should start from the end target and then, from that position, define the rationale of a particular trial. The primary objectives in the first-in-human study always include safety and tolerability.

Of course, a crucial aspect is safety: safety endpoints, such as ECG, vital signs, physical examinations, clinical chemistry, hematology, and so on. There are stopping criteria, which have to be defined beforehand: for example, if a certain amount of serious adverse events happen or a certain level of exposure is reached. Before each dose-escalation step, a safety review committee looks at all data collected and decides whether the dose can be escalated as planned, should stay the same, or be lowered.

When it comes to adverse events, sometimes you will expect certain types of adverse events for your substance, but these will need to be monitored alongside any spontaneous adverse events. All of this knowledge should be put into the study protocol. And if you come up against any challenges, they should always be discussed with the regulatory authorities.

Dicot’s first-in-human clinical trial began in August 2023.

Maximizing the value of regulatory interactions

Unfortunately, there are times when a sponsor reaches out to the regulatory agency for advice and quickly realizes that they have not done things right from the beginning, causing issues and delays. All projects are unique, so consulting with the authorities early and throughout the process is vital for any important decisions. And that could concern almost any aspect of drug development — pharmacology, toxicology, CMC, regulatory issues, and so on.

For LIB-01, we decided to meet with the Swedish MPA and have scientific advice meetings twice at strategic points before the first-in-human trial that would maximize the output of each meeting. An example discussion came from the DMPK and clinical perspective because the prediction of the starting dose was not obvious, and we needed to combine several approaches. Both the starting dose and escalation strategy were discussed and agreed upon with the relevant agencies. Knowing how to proceed with the clinical protocol for the first-in-human study was very helpful and valuable for the project.

Regarding guideline adherence, it’s important to note that guidelines are general by nature. If a part of a guideline doesn’t make scientific sense for your project, you shouldn’t follow it to the letter. However, if you depart from the guidelines covering your area, ensure the relevant authorities are on board with that scientific evaluation.

Final words of advice

-

- Seek help and advice early to avoid common pitfalls and wasting time and money.

- Ensure your project plan is agreed upon by all stakeholders and reconfigure the plan if needed.

- Plan your nonclinical studies from the beginning; not everything needs to be done in separate studies.

- Characterize the effect in animals early.

- Guidelines are not cookbooks, but make sure to speak with the relevant authorities about any deviations.

- Pick a skilled and experienced team to help guide you through the entire process.

- Seek help and advice early to avoid common pitfalls and wasting time and money.

Thank you to Bodil Fornstedt Wallin, Anna Sandholm, Nina Knave, Bengt Hedin, and Jonas Ahlbom for their insights.

About Ulrika Andersson

Ulrika Andersson is Director of Drug Development at Cytel. A pharmacist with 25 years of experience in the pharmaceutical development industry, she has expertise in formulation science, project leadership, pharmaceutical development, and commercial management.

Interested in learning more? Watch our webinar “The Road to First-in-Human Trials: Insights from a Real-World Example”:

Read more from Cytel Perspectives:

Sorry no results please clear the filters and try again

How to Save Time and Limit Costs toward First-in-Human Clinical Trials

Quantitative Strategies for Rare Disease Clinical Trials

Optimizing Early Clinical Development Strategy